A cross-sectional analysis by Professor KD Frick and colleagues examines racial and ethnic health disparities among patients receiving tests to detect cancer.

Cancer screening disparities persist

In a recent cross-sectional analysis of cancer screening rates among race/ethnicity and insurance groups in the United States, two Johns Hopkins Carey Business School researchers found some good news in the push toward greater health equity—though not for all groups.

The retrospective study led by Jingjing Sun, who holds a master’s in Health Care Management from Carey Business School, and economics professor KD Frick analyzed the 2008 and 2018 National Health Interview Survey database, focusing on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening rates. The researchers’ goal: to quantify changes in disparities while assessing the relationship between cancer screening rates, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

“Notably, we found that non-Hispanic Blacks reported higher odds of recent cervical screening in 2018 and mammograms in 2008 than non-Hispanic whites,” says Frick, who holds a joint appointment with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “On the other hand, non-Hispanic Asians consistently reported lower odds of cervical and colorectal screening compared with non-Hispanic Whites between 2008 and 2018 — which points to the need for more targeted interventions in this underserved group.”

There were some other key takeaways of the study, which appeared in PLOS One and was the basis of Sun’s DrPH thesis at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Overall, among all groups, there was an increase in breast screening, from 69.1% to 73%. Colorectal cancer screening rates went up from 54% to 64.9%.

Over the 10-year period, Hispanics increased their uptake of colorectal cancer screening from 36.7% to 59.5% and mammograms, which went from 61.2% to 73.1%. But there were no changes observed for cervical cancer screening rates in this group, which held steady at 78%.

Survey responders who were uninsured were significantly less likely to have had cancer screening across the two time periods for all three types of cancers. In 2018, for example, the overall rate of colorectal screening among the uninsured was 34.5%, compared to a rate of 67.8% for those with private insurance.

What to Read Next

student experience

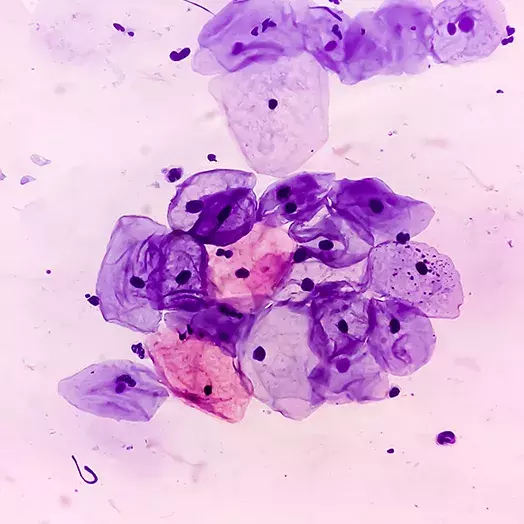

Could artificial intelligence in a “smart tampon” detect cervical cancer?Many factors impact uptake of preventive care

In noting improvements in screening rates for some minority groups, Frick and Sun examined the role of government funding and insurance coverage.

“National-level government-funded programs such as the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program improve the uptake of screening in the low-income, uninsured, and underinsured populations and may account for increased rates among non-Hispanic Blacks and other racial/ethnic minorities,” they note in their study.

Frick further points out that implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which was passed in 2010 and rolled out over the next four years, “played an essential role in increasing cancer screening rates” between 2008 and 2018. The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to encompass millions of low-income individuals who were previously uninsured—people who were disproportionately from race/ethnicity minority groups. In addition, the ACA eliminated cost-sharing requirements for cancer screening, instead requiring health plans to shoulder the costs of preventive screening coverage.

“Of course, it’s important to remember that affordability is just one of many factors that impacts whether people decide to use preventive care,” says Frick. She notes that all three screening tests under study—mammograms, Pap smears, and colorectal screening—can make patients uncomfortable.

“I’ve never heard any of my female friends say they are excited to experience their mammogram or their Pap smear,” she says.

Other factors include changes in the nature and availability, of the screening tests themselves. Frick believes that expansion in colorectal screening options during the 10-year period may have contributed to an overall increase in screening rates for colon cancer. In 2008, colonoscopies—which many people dread, she notes—were the primary option for colorectal cancer screening. New, less invasive options had become more available by 2018, including stool testing.

And pointing to the increase in mammogram screening among the uninsured, Frick observes that the implementation of mobile mammogram units, which brought screening conveniently into low-income neighborhoods, “may have played a role.”

Overcoming cultural barriers

For Frick, the disparity in preventive cancer screening uptake among Asians was perhaps most notable.

“So much of the discussion has focused on Black and Hispanic communities, and the disparities in the Asian community have gone overlooked,” she says.

Observing that some in the Asian community may still be relatively new to the U.S., which could create barriers around language and overall understanding of the American health care system, Frick and Sun suggest that messaging to increase rates of preventive screening must be culturally appropriate. Potential strategies, they note, “could include community-based or workplace-based group educational programs, enhancing cultural awareness among healthcare professionals, and partnering with outreach workers to overcome language and cultural barriers.”

While both researchers were heartened to see some increases in preventive cancer screening among some racial/ethnic groups, they note that more work needs to be done.

“Persistent racial/ethnic and insurance disparities exist among race/ethnicity and insurance groups,” they conclude in their paper, which highlights “the importance of addressing underlying factors contributing to disparities among underserved populations and developing corresponding interventions.”