Carey Researcher Tours Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

It's Such a Good Feeling: Alexandra Klaren examines legacy of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

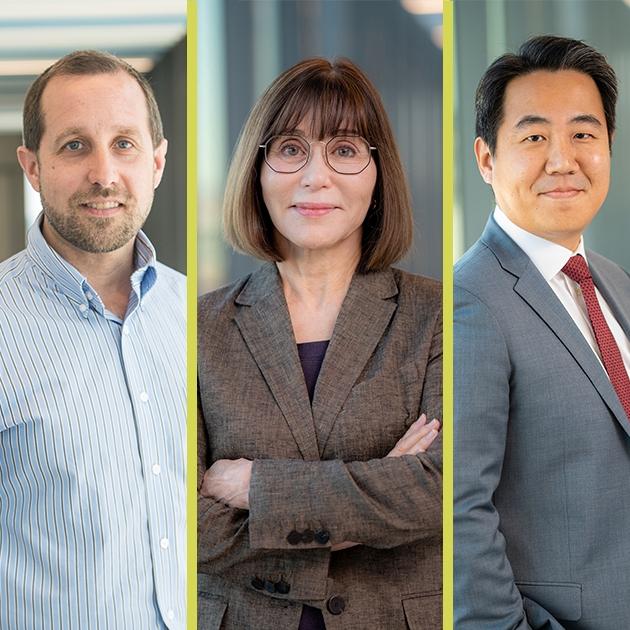

Alexandra Klaren

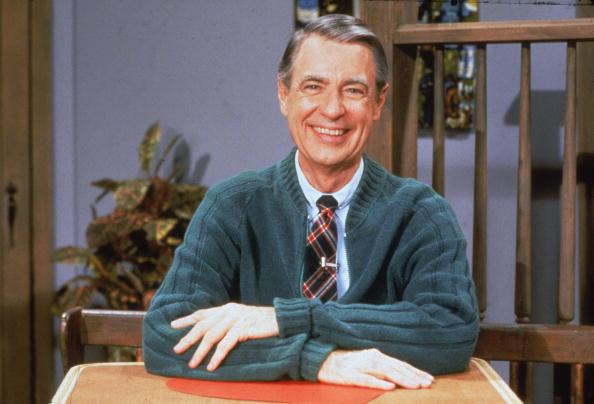

People still love to visit Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Never mind that production of the long-running PBS program for young viewers ended in 2001 and that its creator and guiding spirit, Fred Rogers, died in 2003. How else to explain the recent surge of interest in the man and his show, which are the subjects of a new feature documentary in theaters, as well as documentaries that have recently appeared on PBS and streaming video. That’s not all: A feature film starring Tom Hanks as Fred Rogers is planned for release in late 2019.

Alexandra Klaren, an assistant professor at the Carey Business School, is a lifelong fan of the program. While a graduate student in Pittsburgh, where the show was produced, Klaren wrote her doctoral dissertation on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Last fall in Dallas, her study “Becoming Dialogical: An Inquiry into the Communication Ethics Origins of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” received the top-paper award in the communications ethics division at the 103rd annual convention of the National Communication Association.

In this Q&A, Klaren (right) describes her research, the parallels between her own areas of study and those of Fred Rogers, and some of her favorite moments from the show, among other Rogers-related topics.

Q: Can you describe the central theme and findings of your research on Fred Rogers and the show?

ALEXANDRA KLAREN: My analysis of the show in part explains the uniqueness of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood not as a child’s entertainment program for passing the time but as a relational, dialogical, and pedagogical visit with a caring adult who encourages the child viewer to think about the world and reflect on her role in it. I show how the program fulfilled a need for deep, critical, relational encounters of learning rather than serving, as other programming for children did, as a distraction from the world and self.

More broadly, I offer a rhetorical and cultural analysis of the production, success, and impact of MRN. I locate its emergence in the 1960s in terms of the rise of the television in American family life, and the desire by Fred Rogers to use TV to inspire healthy early child development and to develop a ministry that would use the new medium as a site for moral engagement and discourse with children and their families.

I show that Rogers made a pedagogical, values-based intervention into the then-new medium of TV, where he aimed to counter a children’s TV landscape characterized by chaotic and degrading depictions of human behavior. And he did this by interweaving his studies in child psychology (which included observing and interacting with children) with a Christian understanding of the human person.

The study also analyzes audience reception of the program through an examination and analysis of viewer/fan mail. I argue that Rogers is dedicated to engaging his viewers in a deeply interpersonal form of dialogue that recognizes their shared humanity and affirms individual identities and their development.

Why did you choose this as a research topic?

Growing up in the 1980s and 90s, I often felt that I was immersed in multiple and competing value propositions and messaging via various institutions (e.g., school, family, media, church). Thus, I wrestled with questions about our culture and its values. “How can a plural culture be cohesive with multiple value systems at work within it?” I wondered. “How should we act in the world, and according to which ethical systems?” As a millennial, I was fascinated by the power and influence of mass media productions on the beliefs and attitudes of my peers. So my research within the field of communication has focused on questions of ethics and social institutions, especially the mass media, in contemporary society. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, I think, struggles with tackling the same problems of how to create a moral sensibility and a moral understanding of how to be and act in the world without explicitly communicating in one value systems’ terms.

You earned both your MA and your PhD at the University of Pittsburgh, right in Fred Rogers’s neighborhood, so to speak. What role, if any, did your being in Pittsburgh play in your choice of the topic?

I was looking for a dissertation topic in line with my interests in the intersection of American contemporary culture, media, and ethics. Because I lived and went to graduate school in the heart of Pittsburgh, whose public television station WQED served as the home of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood for around 30 years, I heard that a center dedicated to Rogers’s legacy that included an archive of the program was in the process of being built. I loved the program as a child growing up in Northern Virginia and recall the strength of the relational elements between me and Rogers feeling so strong that I asked my mother to pen a letter to him from me. I remember well the moment when she called to me in the house to notify me that a letter from the Neighborhood had arrived. I opened it up to see a carefully typed note on Neighborhood stationary signed by “Mister Rogers” himself. It also included a black and white, 8x10 photograph of “King Friday,” whose kingly attire I had asked about in my letter. During my research, I found out that Rogers personally replied to each and every letter received at his WQED studio offices.

Given the recent documentaries and the planned film with Tom Hanks, how do you account for this surging interest in Fred Rogers and his TV show? Is it mainly nostalgia among adults who grew up watching the show, or does it go deeper than that?

I do think that during this moment of uncertainty and polarization, our culture is crying out for a noble, reasoned, authentic, and unifying voice like that of Fred Rogers. So in this regard, an examination of this man who meant so much to multiple generations of Americans across the board and who brought people together in a spirit of celebration of the value of the individual and his unique worth, of the promotion of the civic and moral good, and that included an everyday reminder of the importance of moral interpersonal relations within the larger context of a neighborhood community, does seem very much in order.

Do you plan further examinations of Rogers and his work in your research? If so, can you say what that might entail?

I do hope to expand my research on Fred Rogers and his work by engaging in a study of his audience in the form of oral history interviews.

Your MA is in religious studies and your PhD is in communication. That somewhat echoes the background and training of Fred Rogers himself, who was an ordained a Christian minister and a master communicator. Would you reflect on how his sense of spirituality and religiosity affected his work on TV?

Yes, I show how the Neighborhood has a religious source in Protestant Christianity and that the show functions as a kind of Christian ministry despite the lack of specific references to religion. The show, rather, focuses on the ordinary events of everyday life – such as baking a cake, tying one’s shoes, visiting a neighbor – and how these are moments for understanding how to behave in relation with the world and others. Fred Rogers viewed the often violent and debauched, fast-paced, commercial-driven popular media prevalent on TV in the 1960s and aimed to create something radically different. In contrast, his show offered ethically-driven, dialogue-rich substance, which communicated a deep concern for the emotional wellbeing and development of viewers.

In a 1997 speech to the Memphis Theological Seminary, Rogers said that he came to realize that acknowledging the pain he felt as a result of bullying was critical to his own healing and development. “Somehow along the way,” he said, “I caught the belief that God cares, too; that the divine presence cares for those of us who are hurting and that His presence is everywhere.” Although Rogers, in his public persona, did not often emphasize his faith in God very much, his life and philosophy and artistic production was led by his belief in a caring and merciful divinity. “I always pray,” he noted, “that through whatever we produce (whatever we say and do), some word that is heard might ultimately be God’s word. That is my main concern. All the others are minor compared to that.”

As a longtime fan of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, would you share any of your favorite moments from the show?

I loved the time on the program dedicated to what felt like “me and Mister Rogers” time. The show is broken up between the space and time involving the parasocial relationship between the viewer and Rogers – this takes place in Rogers’s home, and sometimes he will take his “television friend” on a visit to a local business or neighbor’s home or factory – and then the realm of fantasy play, where animal puppets and human actors interact in a more dreamlike space called “the Neighborhood of Make Believe.” One of my favorite episodes, and apparently a very popular one among the greater public, includes a visit to a crayon factory, where we see every step of the process of the making of crayons and the mass packaging of them into the cardboard boxes we buy at the drug store. In all his visits outside his “television home,” Rogers placed the workers, craftsmen, salesmen, etc., at center stage. In my dissertation, I write about how in his own personal writings and in the craft of his show, Rogers emphasizes a people-centered, anthropocentric approach to communication, understanding, and everyday life.

About Our Experts