Start Making Sense: New Faculty Member Michelle Barton Studies Ways to Manage Ambiguity

Article Highlights

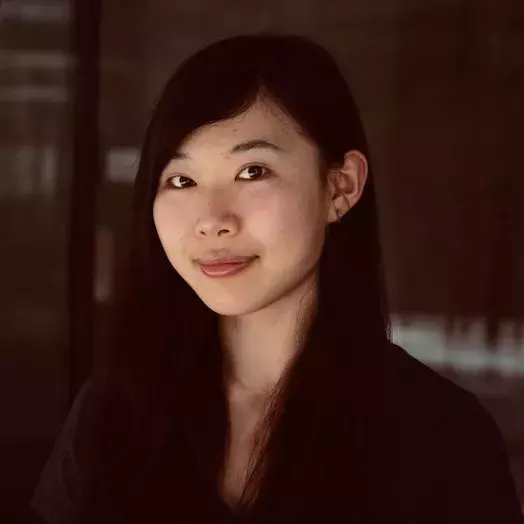

- Associate Professor of Practice Michelle Barton is one of seven new faculty members at Carey.

- She studies the ways groups manage ambiguous, confusing, and adverse situations.

- Like Bloomberg Distinguished Professor Kathleen Sutcliffe, with whom she has worked, Barton has examined group dynamics within the profession of wildland firefighting.

Johns Hopkins Carey Business School Associate Professor of Practice Michelle Barton studies the ways groups manage ambiguous, confusing, and adverse situations. So it’s a safe bet she could find plenty of research material in the events of 2020 – a year marked by inordinately large amounts of ambiguity, confusion, and adversity.

One of seven new faculty members at the Carey Business School, Barton previously served on the faculties of Bentley and Boston universities, and she has conducted research with Bloomberg Distinguished Professor Kathleen Sutcliffe of Carey. In the following Q&A, Barton describes how her research findings might be applied to the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons to be learned from expedition racing and firefighting, and whether leadership can be taught, among other topics (including pie).

Your work focuses on how groups manage uncertain and even volatile situations. Given that we’re in the middle of a pandemic that has killed more than 1 million people and disrupted societies all over the world, what lessons from your work might be applied to help people deal with the current crisis?

Two key lessons: First, don’t ignore emotions. It is common in times of crisis to expect people to “be tough” and focus on the task. But ignored emotions don’t disappear, and, worse, they can create significant problems. Anxiety, fear, and grief tend to trigger defense mechanisms like scapegoating or isolating that undermine people’s ability to work with one another. So, just when we most need people to pull together, they may be most vulnerable to pulling apart.

In my research on resilience, I’ve found that groups that are most resilient – and effective – in the face of adversity are those that explicitly attend to relational issues. One practice I recommend is a “relational pause.” This is a kind of quick huddle to check in with one another on how people are feeling

And second, avoid dysfunctional momentum. One of the biggest challenges when managing uncertain and dynamic situations is simply figuring out what is really going on. When events are evolving rapidly and data is limited, ambiguous, or constantly changing – as they are in this pandemic – it can be tough to make sense of it all. Sensemaking is the process of interacting with our environment in order to figure out “what’s the story here?” and “what should I do about it?”

A major obstacle to sensemaking is that we can get so engrossed in dealing with a situation that we forget to reassess what is really happening – a problem I call dysfunctional momentum. And, if situations are unfolding rapidly, that is dangerous. The solution, which often feels counterintuitive, is to disrupt this momentum by creating interruptions. Sometimes these can be structured into ongoing work processes, like medical “huddles,” but the important point is to use these to deliberately shake up your thinking and look for what is actually happening as opposed to what we assume is happening.

Talking Point

An article that you recently co-authored for BMJ Leader says that resilience “is not just something you have, it’s something you do.” Could you elaborate on that statement?

Resilience is the ability to absorb strain and keep functioning in the face of adversity. But in the groups I’ve studied, this is an ongoing process, and often something people do together. For example, in a recent study of expedition racing teams (similar to the “Eco-Challenge”), Kathleen Sutcliffe and I found that resilient groups did not just endure or “bounce back” from adversity. Rather, they used deliberate strategies to resolve, redistribute, or reframe adversity as they encountered it, constantly coordinating their stores of energy and expertise to fluidly adjust to changing conditions.

These three strategies were grounded in a common assumption: Regardless of who was experiencing the most strain, members acted as if the adversity belonged to the group as a whole. This assumption led to more communal – and effective – approaches to mitigation. For example, by redistributing strain, everyone shared a little extra, but no one felt all of it. For me, the exciting thing about this research is that if resilience is something we do, then we can learn to do it, choose to do it, and help others do it, too.

The co-authors of the BMJ Leader article include Kathleen Sutcliffe and Assistant Professor Christopher Myers of the Carey faculty. Like Professor Sutcliffe, you’ve examined group dynamics in the contexts of wildfire fighting. In what specific ways do those two activities lend themselves to the type of research that you conduct?

Wildland firefighters, like many organizational groups today, grapple with contexts that are dynamic, complex, and often adverse. Wildfires are notoriously unpredictable, jumping from place to place or escalating from slow smolder to huge conflagration in moments. Wildland firefighters must update strategies with incomplete information, while coordinating everything from food and shovels to fleets of aircraft, often without reliable communication channels.

There is a reason that managers struggling with a sudden crisis at work say that they are “fighting fires.” Like expedition racers, firefighters represent a kind of microcosm of team dynamics under conditions of uncertainty and adversity, and thus offer rich insight into processes like sensemaking and resilience.

“I come down 100 percent on the side that says leadership can be taught. Leadership is a skill, like playing tennis or baking. Sure, some traits might prove helpful, though these are often not the ones you would assume. Many good leaders are introverts. The best leaders are those who can ask for help, who look to develop powerful systems, rather than personal power, and who are willing to be deeply self-aware.”

Michelle Barton, Associate Professor of Practice

As someone with experience running leadership training programs, can you say to what extent leadership is something that can be taught – and to what extent is it largely an inherent trait in some people, like an ear for music?

I come down 100 percent on the side that says leadership can be taught. Leadership is a skill, like playing tennis or baking. Sure, some traits might prove helpful, though these are often not the ones you would assume. Many good leaders are introverts. The best leaders are those who can ask for help, who look to develop powerful systems, rather than personal power, and who are willing to be deeply self-aware.

In any case, I believe leaders are no more born than are great athletes. If you asked Michael Jordan if he was born a great basketball player, he might (with some justification) be a little irritated. He worked his you-know-what off to get to his level of skill. Sure, his athleticism and height help – but there are plenty of tall athletic people who don’t become star players. He took what he had, and then he practiced. And, while it might be harder for a short, pudgy person to become a basketball star, I think just about anyone can become a leader. But it takes humility to be a good learner (and if you believe you were born to lead, you may already be behind the eight ball there).

How have the pandemic and the resulting lockdown conditions affected your work?

I’ve been incredibly lucky. Both my husband and I can work from home. Obviously, the lockdown is unsettling, but it has not stopped my work. In fact, I feel like we are both busier than ever, perhaps because there is so little divide between home and work. But I love my 30-second commute.

Are you teaching any classes during the 2020-21 academic year?

Yes, I am teaching three courses: Power and Politics, Negotiations, and Leadership in Organizations. What do you like to do for fun or relaxation when you have free time? Ha ha ha. … OK, mostly I live vicariously through my two sons who are away at college and have all sorts of interesting hobbies. But when I have a few moments, I read for fun, do free-hand embroidery for meditation, hike for exercise (not nearly enough), and, like so many others during this pandemic, bake. I make a great cherry pie.

What to Read Next

research

New Faculty Member Jessie Liu Works Where Economics and Marketing MeetAbout Our Experts

Michelle Barton’s expertise is in organizational and team resilience, managing uncertainty, and interpersonal effectiveness during adversity. Her work examines how groups manage dynamic and uncertain situations as they are unfolding. Drawing from wildland firefighting, high tech entrepreneurship, expedition racing, and military operations, her research considers how groups make sense of ambiguous situations, how they coordinate, learn and share knowledge in the midst of confusion and how they mitigate and recover from adversity. She is especially focused on the relational dynamics that enable these practices.