Assistant professor in research track, one of seven new members of Carey’s full-time faculty, arrives after earning her PhD in economics from Penn.

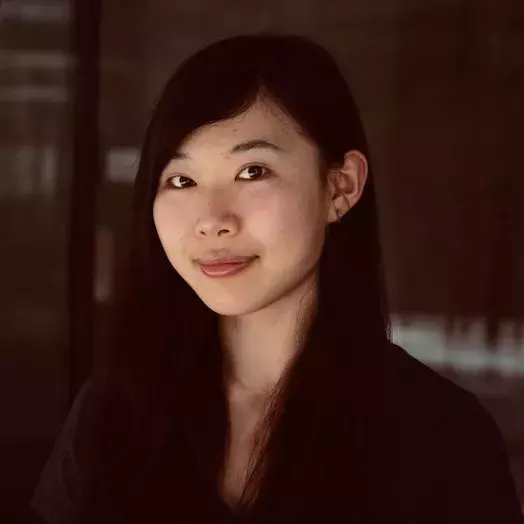

New Faculty Member Jessie Liu Works Where Economics and Marketing Meet

Article Highlights

- One of seven new Carey full-time faculty members

- She’s an economist whose work often involves elements of marketing.

- Specialties include media economics, online censorship, and luxury goods.

Among academic researchers, the intersection of economics and marketing has become a well-traveled junction.

A recent addition to the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School full-time faculty, Assistant Professor Zhenqi (Jessie) Liu, is one of those researchers whose work often blends the two disciplines.

In the following Q&A, Liu discusses her research interests – including media economics, online censorship, and luxury goods – her teaching plans, and the ways in which the pandemic has affected her work.

---------------------------

QUESTION: From a business school’s perspective, economics and marketing are generally regarded as two separate disciplines. But as we’ve seen in the work of economists not just here at Carey but elsewhere (and including your own work), there seems to be considerable overlap between economics and marketing. Why do you think this overlap between the two disciplines exists?

ZHENQI (JESSIE) LIU: I think economics (particularly microeconomics) and marketing are interrelated disciplines that inform and influence each other because they share a common interest in studying the interface between firms, competitors, and consumers.

Could you explain what’s meant by “information and media economics,” which you list as one of your research interests?

A: It refers to combining the study of situations in which different economic agents have access to different information and the study of media. Most of the decisions taken by those who run media organizations are, to a greater or lesser extent, influenced by such informational asymmetries. Media outlets, for example, may fail to disseminate certain viewpoints or choose to engage in propaganda campaigns, so as to cater to the tastes of majority consumers or to differentiate ideologically from competitors for economic benefits. Economics, as a discipline, is thus highly relevant to understanding how media firms and industries operate.

One of your working papers concerns “evidence of online censorship in China.” Could you describe the main theme and findings from this study?

A: This study examines the role of market structure in regulatory compliance through a unique empirical example: censorship via content removal by three major live-streaming platforms in China. Adopting an event study approach, my research exploits the unexpected occurrence of 30 salient events over two years and shows that platforms of different sizes censor a different number of keywords with notably different delays.

Motivated by the empirical facts, I further develop a structural model to analyze the compliance incentives of those platforms in a competitive market. By complying with the government’s censorship request, platforms may lose users who prefer to evade censorship by switching out. By not complying, platforms incur a cost imposed by the government that is positively correlated with their sizes, but it also allows them to attract new users from competitors that obey the censorship requests. While large platforms censor more often than their small competitors due to higher political cost, centralizing market power via merging or shutting down small platforms does not necessarily generate more censorship in the marketplace.

My findings suggest that decentralizing online market power may help an authoritarian government maintain a sufficiently high market level of censorship in an overall low-pressure environment: Tolerating a bit of dissent on small platforms allows large platforms to censor more effectively as it mitigates their strategic incentives. This might be one of the reasons why, unlike the U.S. market, which is dominated by a handful of mainstream social media platforms, Chinese social media is still fragmented and localized.

“Media outlets may fail to disseminate certain viewpoints or choose to engage in propaganda campaigns, so as to cater to the tastes of majority consumers or to differentiate ideologically from competitors for economic benefits. Economics, as a discipline, is thus highly relevant to understanding how media firms and industries operate.”

Zhenqi (Jessie) Liu, Assistant Professor

You’ve also done work on the pricing of luxury goods. What have you found from that area of your research?

A: From a practitioner’s perspective, luxury sets the price – higher quality and better craftsmanship of a luxury good allow for its premium pricing. For academic scholars, the higher price creates luxury – the wealthy self-select into buying luxury goods to credibly showcase they have “money to burn.’’ This helps them to be distinguished and attain better outcomes socially, romantically, and professionally, while maintaining the exclusivity of a luxury brand.

However, this thesis of conspicuous consumption signaling wealth is facing some serious challenges for its validity, in the presence of counterfeits that look almost identical to the authentic luxury goods. If counterfeit goods are identical in appearance to the authentic ones, and they are available at very low prices, then more spending on more luxury goods can no longer serve as an effective signal for wealth. My recent work looks into this new market environment and investigates how buying less can paradoxically become a new form of conspicuous consumption. Importantly, we show that the damage inflicted on a luxury brand by counterfeits comes not only from those who switch to counterfeits but also from those who never purchase counterfeits. Thus, a single-minded focus on counterfeit users in combating counterfeits could be misplaced. Moreover, the arrival of high-quality, low-price counterfeits can fundamentally transform the luxury goods industry: The consumption behavior associated with luxury goods may no longer be an exclusive signifier of wealth. As a result, consumer segmentation based on income need not always be optimal for a luxury brand.

What to Read Next

research

Curiosity Created a Career: How New Faculty Member Alec Brandon Became an EconomistCan you describe any other current or upcoming research projects you’re working on?

A: I am currently working on two other projects: one on how the rollout of the digital privacy policy (such as general data protection regulation, or GDPR) affects consumers’ online engagement, and the other on influencer marketing.

Are you teaching any classes during the 2020-21 academic year?

A: I will be teaching Customer Analytics in the spring semester.

How have the pandemic and the resulting lockdown conditions affected your work?

A: On the one hand, the pandemic and subsequent travel bans have complicated some of my research that requires in-person data acquisitions. Besides, several workshops and conferences I normally would have attended were either canceled or postponed. On the other hand, the pandemic also made many high-profile seminars accessible to a wider audience as they moved online.

Whenever you have free time, what do you like to do for fun or relaxation?

A: Lately, I have had a lot of fun playing the ukulele and hiking in the woods.