A new study, authored by Carey Business School Professor Tinglong Dai, finds an association between publicly traded companies and recalls of AI-based medical tools.

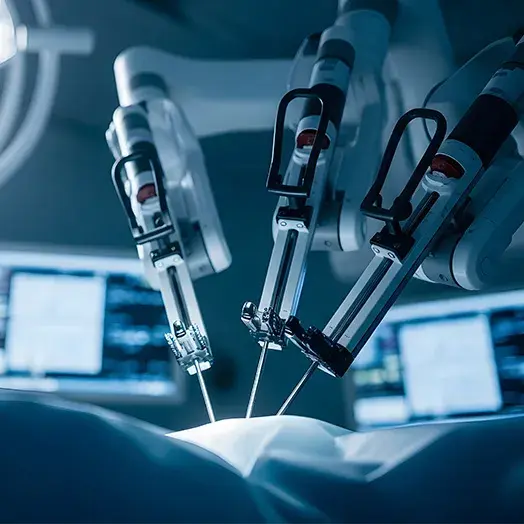

Is investor pressure driving risky AI medical device launches?

AI is transforming health care, but are we moving too fast to integrate the technology into clinical settings? A new study from Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and Yale researchers suggests we might be. Their analysis of nearly 1,000 AI-enabled medical devices, or AIMDs, approved by the FDA found an alarming trend: devices from publicly traded companies are far more likely to be recalled, and many hit the market without being tested on real people.

The research, published in JAMA Health Forum raises concerns about the FDA’s current approval process of these devices and the risks posed to patients. According to the authors, the association between AIMD recalls and public companies could reflect an “investor-driven pressure for faster launches of products,” warranting further investigation.

Publicly traded firms accounted for just over half of the AIMDs studied (53.2%) but were responsible for more than 90% of the recall events. These companies were nearly six times more likely to have a device recalled than privately held firms. Among the recalled devices from private companies, 40% lacked clinical validation, also known as real-human data analysis or testing. That figure rose to 77.7% for established public companies and a staggering 96.9% for smaller public firms.

“The lopsided nature of these recalls should give every advocate for medical AI pause,” said Tinglong Dai, corresponding author and the Bernard T. Ferrari Professor of Business at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. “Publicly traded companies, the big fish in this still-small pond, built just over half the devices but were responsible for nearly all the recalled units.”

The study also sheds light on the FDA’s 510(k) clearance pathway, which allows devices to be approved without prospective human testing. This pathway is commonly used for AIMDs, meaning many of these tools reach patients without being evaluated in real-world clinical settings. The consequences are significant: 43.4% of AIMD recalls occurred within the first year of clearance—about twice the rate reported for all 510(k) devices.

“We were stunned to find that nearly half of all AI device recalls happened in the very first year after approval,” said Dai. “And the even bigger surprise? The recalls were heavily concentrated among tools with no reported clinical validation whatsoever. We just thought, ‘wow — if AI hasn’t been tested on people, then people become the test.’”

What to Read Next

health

Urban hospitals claim rural status for Medicare gainsTo address these risks, the researchers propose several solutions, including requiring human testing or clinical trials before a device is approved, incentivizing companies to conduct ongoing studies after launch, and collecting real-world performance data to ensure continued safety and effectiveness. They also suggest that approvals could be made conditional, expiring unless evidence shows the device works as intended.

“If these tools are going to scale, we’ve got to test them on real people,” Dai emphasized. “Either require proper human studies up front or give approvals that expire unless the evidence shows they actually work.”

In addition to Dai, authors include Joseph S. Ross, a professor of medicine at Yale University School of Medicine; Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean for public health practice and community engagement at Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; and medical students Branden Lee, Patrick Kramer, Sara Sandri, Ritika Chanda, Crystal Favorito, and Olivia Nasef.